In the proliferation of analyst reports on this Shenzhen-HK Stock Connect (approved by the National Development and Reform Commission on 16 August), there is clearly a wave of positive comments and praises for the scheme in fostering China’s capital account liberalisation, on- and off-shore market convergence, RMB internationalisation, improvement in capital allocation and MSCI inclusion of A-shares. I agree with most of them. But some blind optimism and erroneous views need to be clarified.

Optimism is justified…

This Shenzhen-HK Stock Connect scheme could potentially be a game changer for investment in China by allowing international investors access to the universe of “new China” stocks in technology, media, healthcare, communications, and consumer services companies listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. Currently, three companies: Alibaba, Tencent and China Mobile account more than 50% of the market cap of the “new China” stocks in the MSCI China index. The new Connect will offer hundreds of choices to foreign investors to monetaise the new growth engines of China.

The abolition of the annual net quota of the Shanghai-HK Stock Connect to coincide with the decision of not setting an annual quota for the Shenzhen-HK Stock Connect is a step towards liberalising the capital account and, in principle, deepening the internationalisation of the RMB. Crucially, in a balanced market where selling and buying forces are equal, trading under the Connect scheme will go on uninterrupted because the net buy quotas will not be hit. All this will help improve Chinese stock liquidity and is instrumental in improving the chance for MSCI to include A-share in its global index.

…but blind optimism is not

While the benefits are obvious, clarification of some distorted views in the market is needed. Some analyst from a major player argued that “the abolishment of overall quotas can be seen as an indication that China’s capital liberalisation is maturing…” This is a causal and irresponsible statement unsubstantiated and refuted by research evidence. But still, it has brought some followers!

The Chinn-Ito index, a measure of capital account openness of 181 countries in the world with a scale of 0 (completely closed capital account) to 1 (completely open capital account), shows clearly that China’s capital account was quite closed as of 2014, the latest update available (see Chart). Its opening-up process is still at an early stage, as we have long argued.

The introduction of the Shanghai-HK Stock Connect scheme in late 2014 would not by any remote chance have boosted China’s capital account convertibility in any significant way because, as I argued earlier (see “Chi Time: Hong Kong-Shanghai Mutual Market Access (II): Inching Towards Capital Account Convertibility”, 8 October 2014), the scheme is only a baby step towards liberalising China’s capital account. Due to the closed-loop design of the Shenzhen-HK (and also the Shanghai-HK) scheme, it does not really allow free capital flows in and out of the country. It only extends the boundary of capital controls over mainland Chinese capital to Hong Kong, and it does not allow price arbitrage between the onshore and HK markets for inter-listed stocks (see reference above).

Furthermore, the regulatory requirement of all FX trades for settling the Stock Connect trades to be done in Hong Kong clearly shows that Beijing still intends to keep the onshore market segregated from the offshore (Hong Kong) market by using CNH liquidity only to support the Stock Connect schemes. The purpose is to shield the onshore monetary regime from offshore volatility (see “Chi Time: Hong Kong-Shanghai Mutual Market Access (I): The Liquidity Conundrum”, 15 September 2014).

Others also argue that the daily net quotas are a risk control measure against speculative flows. This is only partly right. It cannot deny the fact that these quotas, together with the closed-loop cross-border flow design of the schemes, are still capital controls. Risk can be controlled through a circuit breaker mechanism, which China tried but failed, instead of quotas.

If the Shenzhen-HK scheme assumes the same trading/demand pattern as the Shanghai-HK scheme, where there are significantly more southbound trades than northbound (the southbound trades used up 85% of the annual net quota in the past year while the northbound trades only used 40%), the new scheme will shrink the offshore (Hong Kong) RMB pool further. Ceteris paribus, this will not be conducive to RMB internationalisation, as some observers assume.

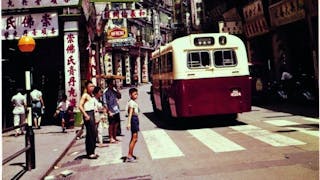

(Cover Photo: Eye Press)