Recently, while senior officials in Beijing were busy preparing for the Belt and Road Forum and the Chinese Football Association was preoccupied with ensuring that its representative was elected on May 8th into the FIFA Council, football’s global governing body, ordinary Chinese, and football fans, have been obsessed with a television drama.

Candid portraits of corruption

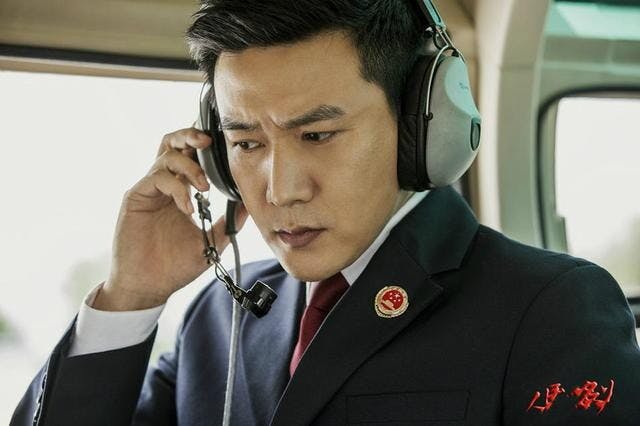

In the Name of the People is perhaps the most talked-about TV series in China since March this year.

That this 52-episode series – broadcast first by Hunan Satellite TV, an acknowledged trendsetter, and then by many online channels – has made candid portraits of corruption at multiple levels, many of which bear clear references to real-life personalities and events, has surprised even the most jaded observers.

Shows that deal with the unseemly side of life have been absent from the TV screen since media watchdogs in the mid-2000s decided that such content might reflect poorly on the country’s image.

But this show has managed to avoid the censors’ cuts.

Of its many twists and turns, the show depicts rent-seeking behavior, misappropriation of land and mining resources, and party politicking.

But it also has a few scenes on sports – football and basketball, in particular – with intriguing messages that perhaps only sharp viewers would appreciate.

Ugly side of ‘beautiful game’

The unlikely “hero” who breaks the silence and spoils the scene is a 12-year-old schoolboy nicknamed “Little Ball”. The somewhat rebellious, street-smart kid offers a stark contrast to his sober-looking father, who is the local anti-corruption bureau chief.

When Little Ball is asked by Hou, a supercharged investigator of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and a friend of his father, to explain the boy’s rather delinquent behavior while playing football at school, Little Ball confesses that he had paid 10 yuan to the team captain and 5 yuan to the deputy for a place in the first team.

Six other students did the same, but they still ended up on the bench.

The boy’s statement visibly shocks Hou, a seasoned corruption investigator who perhaps didn’t quite expect that the practice is so deeply rooted in society that even schoolboys do it.

This scene has drawn lots of interest because it reminds football fans and viewers of a rather dark history of Chinese football in the not-so-distant past.

Before the current wave of policy impetus and investment spurs began in 2014, Chinese football had been in the spotlight for the wrong reasons.

Behind the rebranding of Jia-A League into China Super League in 2004 lay millions of yuan of investments by commercial sponsors.

The heightened stakes, when combined with the unchecked power lurking at many layers of the administration of the game (the clubs, match officials and, ultimately, the governing body), brought out the ugly side of the “beautiful game”.

In the end, as the pie, be it football success or financial reward, couldn’t be shared evenly, a series of astonishing revelations and scandals swept through news headlines and tarnished the sport.

It all culminated in corporates exiting the scene, clubs being knocked down to the lower leagues, and officials at the top of the powerhouse being brought to justice in 2010.

Rampant use of red pockets

Since then, no new scandals about match fixing and corruption have visited Chinese football.

While there are complaints by clubs and individuals about game results and perhaps favoritism toward or against individual clubs or players, there has been no repetition of the large-scale collusions seen in the early 2000s.

However, anecdotes can still be picked up regarding the jockeying for positions by players.

In May 2015, a blog titled “Breaking news by an insider of the national team … 1.6m (yuan) for a first team place” went viral.

It drew out the frustrations of millions of football fans who were disheartened by the lame performance of the national team in the 2016 World Cup qualifying matches.

Blaming the poor quality of football played by the national team on a system comprising of layers of money sucking by clubs officials, scouts, agents, coaches and even school PE teachers, the blog’s author extended the censure all the way down to the parents, who were only too eager to help their “only child” to muscle out competitors through the rampant use of “red pockets”.

Playing the game he likes

While the attempt at the 2018 World Cup by China’s national team is likely to yield yet another disappointment – China is now second from the bottom in the final qualifying round with only a slim, mathematical chance of getting through – one of the TV drama’s closing scenes is spot on.

After the dust of the previous turmoils has settled, the party secretary arrives at the trouble-plagued province to play a friendly game of basketball with colleagues comprising mostly of local officials.

During the break, he is told that the basketball court was freshly converted from a tennis court. His predecessor, who has been convicted of corruption, liked tennis.

A close ally then quotes the ancient philosopher Mozi: “As the King of Chu (a kingdom of warring states) liked men with small waists, many officials died while going on a diet.”

Many viewers regard it as the most telling line in the entire TV drama.