In the world of sports business, March 2020 could be remembered as once-in-a-century “time-out” of a match with corporate players coming from around the globe. League games are halted, tournaments cancelled, events postponed. Even the Olympic in the summer has to be pushed out for about a year. While global players are collectively experiencing a break, a playbook of crisis management has started to emerge and its springboard seems to come out from an unlikely place – China.

We are all down together

The sports business is both local and international. Many leagues have distinctively local (country, regional, even city) rules and participating rights. However, the laws of most games, their fans and sponsorships are generally global in nature. As such, it should not be surprised that while everyone feels similar pain, those who could learn and react quicker from places where cycles are more advance and apply the drills more swiftly than the others may be able to come off bench sooner.

Being the first in the globe to face nation-wide lockdown and travel bans, civil and commercial traffic in China ground to a halt starting at the end of January 2020. Shops and factory closures were expected for the Chinese New Year anyway but this epidemic-led closure has been a totally different ballgame.

Global players and local titans feel the recent plights with no exception. Nike, the world’s largest sports company by market capitalization, announced on as early as the 5th February that it would close down half of the retail shops it runs in China in the face of the spread of the disease. A host of international names including adidas, Puma, Lululemon, Under Armour wasted little time to shut down the shops hoping to contain the effect of the virus. Similarly, local names such as Anta, Fila, Li Ning and Xtep who are under the street-level supervision by units which are eager to contain the virus, have limited choice but to close most of their off-line shops. Unlike their international peers, most of these domestic players (save Anta) do not have geographical diversification at their disposal to fend off the impact.

However, it is in the “zero and one” that they find the lifelines. While smartphone penetration and, with it, e-commerce and mobile internet have endeared online shopping to Generation X in China for a good, few years, the extent of this digital disruption can only be revealed by this pandemic-generated disruption.

But not all are out

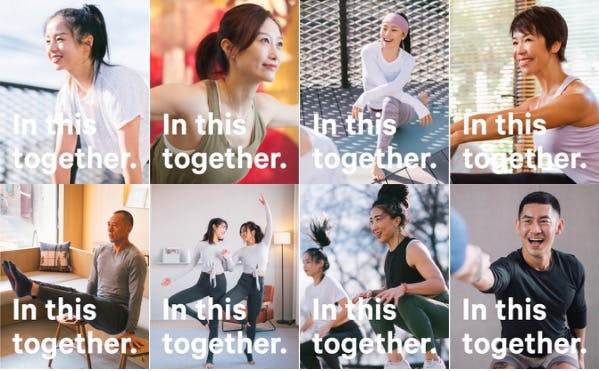

Take Nike for an example. The biggest sportswear brand in Greater China generated about US$7bn sales locally in FY2019. During the last two months, it has turned to online space. Not just for the erection of digital “sales outlets” with banners of discounts and coupons, tired tricks of yesteryears’ online promotions, it has also “engaged” actively with the health-conscious, WFH (“work-from-home”) executives. Teaming up with famous sportspersons, “Big V” (Chinese version of KOLs, or Key-Opinion-Leaders) and media celebrities, its app in China is packed with video clips of personal training and workout sessions. Many interactive features are newly added. The new approach has proved critical at a time when the entire nation is essentially frozen and workplaces emptied. Engagements, especially the ones through Douyin (otherwise known as “TikTok” internationally), Bilibili (alias, the “B site”) and other popular video-sharing channels many having a duration as short as just 15 seconds, has become the preferred way to connect brands with their fans and their purses.

In March 2020, Nike became one of the “IP sponsors” (alongside title sponsors like Mengniu and Darlie) of a talent show “Youth with You, Series Two” which has been screened on iQiyi, a popular online video platform. In an average episode, the reality show would, some industry watchers have counted, display the iconic swoosh as many times as an average 90-minute football match would.

Reflecting on this China’s experience, CEO John Donahoe cited it as providing THE playbook. Donahoe, whose CV tells a career in tech industry including eBay and ServiceNow, said last month in a conference call with equity analysts, “we are seeing the other side of the crisis in China…we now have a playbook we can use elsewhere.”

Another sports brand which has been proactively learning from China to enrich its global tool kits is Lululemon, the world’s third-largest sports company by market capitalisation. The Vancouver-headquartered company, famous for its ultra-slim yoga pants has till last fiscal year North America as its primary revenue base. Out of its 491 global shop counts, it runs 305 and 63 shops in the US and Canada. China’s count is at its third, with 38.

In the latest earnings call with analysts in late March, Calvin McDonald, CEO, echoed Donahoe and said, “we have early learnings from China which show us that our business will bounce back…Our teams in North America and Europe have followed the lead of our people in China where we have gained thousands of new followers on WeChat.” This comes with no surprise because earlier in January, Lululemon hired Nikki Neuburger, a veteran Nike senior executive once responsible for the latter’s digital innovation. Since February, the firm’s near 30 men/women strong ambassadors have been actively giving out free yoga lessons through social media networks like Douyin and Keep (a “unicorn” and an app dedicated to self-training).

Subtle Difference, Material Impact

Distinct strategies employed to deal with this global crisis can be told from the subtle difference in the management characterisation of their experience in China. Adidas, the German sports behemoth and the world’s second-largest sports company by market capitalisation, has a different take on their experience in China. Kasper Rørsted, who has been at the helm since 2016, described in an earnings call with analysts the two-month (till March) experience in China and the implication to the rest of the world as “spillover”. Considering “…the impact we have had in China because we want to protect the rest of our business,” the once handball national player (for Denmark) and sales executive of Compaq Europe was keen to make sure that “protective” measures are put in place. Rørsted added, “we have divided our business into two and think how do we defend…so we don’t have a spillover effect from the Chinese side.”

This is not to say the three-stripes has shut down for business. China has contributed nearly a third of its revenue still. In fact, it made a splashing hit by a digital launch in mid-February of its important “Superstar 50 (anniversary)” series on Taobao with two KOLs staging a live broadcast to compete and sell shoes. The event registered about 2.2 million online participants, a number far exceeding what it would have attracted had it been held in a hotel or exhibition hall. However, selling products and clearing inventory could be considered just part of the jigsaws to connect with people, especially in today’s environment where consumers perhaps need something more inspirational than just material possession.

At the time of writing, Nike’s share price is down by 14% from its all-time high in mid-February, recovering from the once jaw-dropping 38% fall during the trough in late March. Similarly, Lululemon has rebounded from mid-March’s slide of -47% from February’s height to land at just about -19%. On the other hand, adidas has still had a catch-up game to play, with its shares currently down by 29% after registering a recent low at about -41% in March. For comparison, the S&P 500, widely considered as the barometer of the broader market, is down by about 16% as of the end of last week.

The playbook from China may still have pages to add, but for now, there seems to contain some useful drills from which one can apply in this battle against the invisible assassin.