In Hong Kong, there is a little-known world champion sitting with us every mid-week and weekend, namely the winner of the English Premier League (EPL) broadcasting rights. In terms of the acquisition cost of the rights for EPL and on a per-head basis, the broadcaster here has been paying the highest amount globally, outside of the UK.

An English tradition

Nowadays, most people pay to watch the sport and follow the teams that they support through TV, or more likely, through a mobile phone or the internet. Paying for the subscription is as natural as paying the bills after a meal, or for the tickets to watch a movie or concert.

However, this habit has not come around for a very long time.

Take the EPL, or more appropriately, the First Division of Football League (as it used to be called before 1992) for example. Although television had been around and become more and more popular since the 1950 and 60s, football matches were not screened on TV very often because back then, football clubs saw TV broadcasts as competitors to their match day revenue. So the clubs were highly selective and cautious in releasing TV rights.

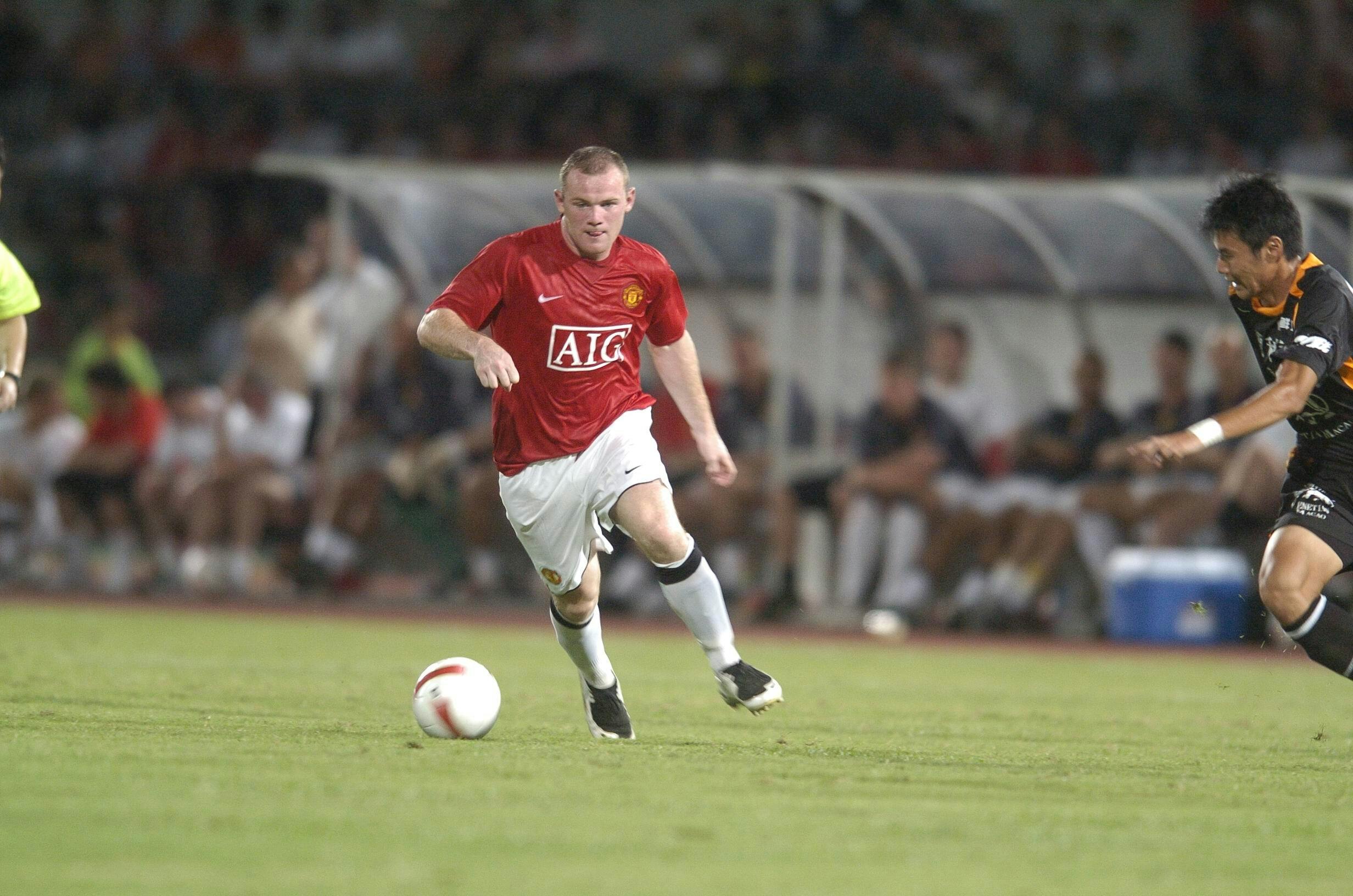

During the 70s to 80s, the most that TV viewers could watch were the programs and live matches on The FA Cup that was jointly promoted by the Football League and the BBC. Partly as a result of this screening tradition, in those days, teams such as Tottenham Spurs or Manchester United, which didn’t perform consistently in the season-long league battleship but had outstanding talents that could, on their days, produce moments of magic, could manage to draw huge followers domestically and internationally, rivaling the more successful league leaders like Liverpool and Arsenal.

A dramatic breakthrough took place in 1992 when BSkyB, a newly-emerged pay-TV operator controlled by Australian media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, sealed a deal with the twenty-two first division clubs to break away from the Football League. Together, they formed a revamped and rebranded Premier League. Since then, with a massive influx of TV money arising from the exclusive airing of the games, the sport has finally embraced media to form a partnership.

The arrival of new media such as the mobile phone and the internet has inflamed further the value of the media rights for the EPL and its composite clubs. For instance, it was widely reported that the current three-year broadcasting deal which will last till 2019 locks the domestic rights at an eye-watering 5.3 billion pounds, or more than 1.7 billion pounds per year. The hefty amount is some 44 times the value of such rights in 1992, its inaugural year and compares favorably to the “mediocre” three-fold increase of FTSE (All-Shares) Index measured for the same period.

Hong Kong’s world-class winner

If what happens in England is just “ship floating high under a rising tide”, what is going on in Hong Kong, a city of more than 7 million people, is “threading high through the cloud and fog”, as someone put it.

Hong Kong, among Asia’s top cities, regions or countries, has been one of the earliest adopters of pay-TV. Of course, in its early days, there was similar push back on media by the local football clubs which saw TV as a threat to ticket sales, the bread and butter of the clubs then.

But as time went by, the allure of the EPL became irresistible with a generation of footballers who looked good on TV while still managed to play entertaining and attacking games. The competition for viewers between TV and clubs became a non-issue as the appeal of local football games faded out.

Another parallel was that the emergence of new media transpired to unlock hitherto untapped demand. When EPL played its first kick in 1992 in England, Hong Kong witnessed the birth of a new pay-TV station, namely i-Cable (it was called Cable TV in its early days and has been owned and operated by Wharf, a leading property conglomerate) in 1993. Back then, one of its “killer applications” was the exclusive rights to EPL, rights which reportedly cost about US$1 million for a three-year deal between 1996 and 1999, or around US$330,000 per year.

Over the years, the rise of ESPN (a sports channel and a subsidiary of Disney) as part-competitor and part-collaborator to i-Cable, and of NOW TV (another pay-TV operator, which was founded by PCCW, a dominant fixed-line operator), served to heat up the competition for broadcasting rights. Each turn of the three-year rights has become a major arena for groups to showcase their financial muscle and negotiating power.

The year 2016 further saw, almost out of nowhere, the pop-up of a then little-known player in HK’s pay-TV scene in the form of LeTV, a mainland China-based, internet equipment-turned content and media platform. The amount LeTV paid for a three-year contract ending 2019 was reportedly a sky-high US$400 million, double the amount previously paid by NOW, and translating to over US$130 million per year.

This new height has helped Hong Kong clinch a victory in term of global broadcasting rights. If the amount is to be divided by the size of the population, the price per head in HK is, other than that of the UK, the highest in the world – Hongkongers pay approximately 12 pounds per head (about US$18, using the then prevailing exchange rate). While Britons spend about 26 pounds, the third place goes to Norway where the people pay approximately 9 pounds per head.

With this, it should be clear to everyone that the games on the TV screens are only part of the battle.

The real and perhaps more exciting ones take place behind the scene. Now, if anyone thinks that sports in Hong Kong do not contribute much to the GDP, it may just be that they seldom turn on the TV at night.

We are authorised to republish the article from the author.