中文摘要:P2P金融平台自2006年起興起,到2015至2016年間出現第一波爆破,令一些投資者聚集在銀保監總部門外抗議,促使北京政府推行10項措施以鎮定公眾情緒。在中國創新過程中,這場P2P風波暴露了其在監管與激勵方面出了毛病。例如相關部門要監管P2P活動及執行法律,但人手嚴重不足,而地方政府亦無從看管一些橫跨數個司法管轄區的P2P平台。

作者認為,P2P平台與銀行有別。一旦出現貸款出事,銀行有義務將款項歸還予存戶;反觀P2P平台則只是中介,一旦出事,都不會擔保或賠償。然而中國在這範疇的界線模糊,許多P2P平台要不是龐氏騙局,就是地下銀行。即使銀保監於2016年8月曾劃定這類行為屬於非法,但今年6月出現的P2P危機,則證明中國在這範疇仍然沒有法規。幸而P2P貸款規模不大,截至今年7月P2P貸款佔銀行貸款、資產各不足1%,不太可能衝擊中國金融體系。不過,P2P危機仍然是一個結構性問題,中國政府在進行金融現代化的同時,亦須着力解決上述問題。

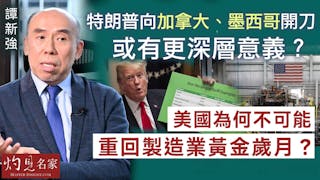

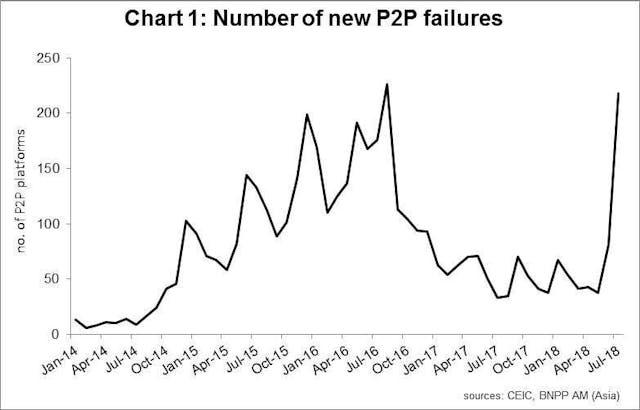

Once touted as a way to transform China’s financial sector to allocate capital more efficiently by market forces, China’s online peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platform has collapsed. The number of new P2P failures has surged again since June 2018 after an initial wave of failures in 2015-16 (Chart 1), sending the outstanding amount of P2P loans plunging (Chart 2).

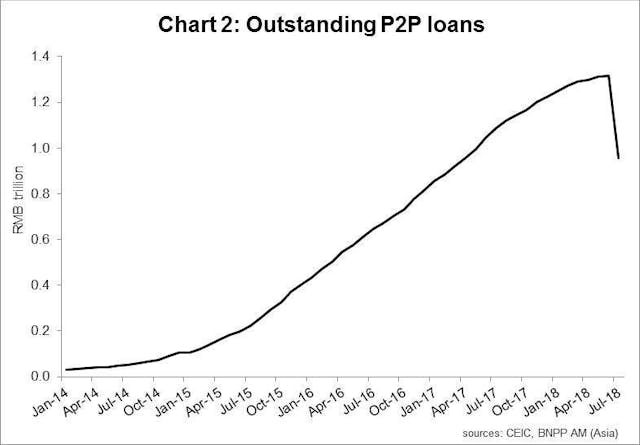

These platforms emerged in late 2006 by connecting individuals looking to borrow money with those willing to lend directly to these borrowers without going through the traditional financial intermediaries. The model took off between late 2014 and 2015 (Chart 3) amid a massive boom in internet finance.

Retreat from implicit guarantee backfires

The first wave of failures between 2015 and 2016 did not cause any financial panic. Indeed, the amount of P2P loans continued to grow during that time (see Charts 1 and 2), reflecting a consolidation process of inefficient platforms exited the market.

However, the recent failures have triggered a confidence crisis with news on mom-and-pop investors losing all of their lifetime savings, committing suicide, demonstrating outside the CBIRC headquarters in Beijing demanding justice etc. flooding the Mainland media and even triggering internal criticism on President Xi’s policy direction.(註1) All these prompted Beijing to roll out 10 measures to counter online lending risk in early August to calm public sentiment.

The current panic is most likely caused by the retreat by the CBIRC from the implicit guarantee policy. In mid-June, Guo Shuqing, head of the CBIRC, issued a stern warning that people should prepare to lose their money if an investment promised 10% returns or more. Until then, people believed that the close relationship between P2P companies and local governments underscored blanket state support of P2P investments.

P2P lending, underground banking and incentive problem

The P2P debacle reveals both supervisory failure and a serious incentive problem in the China’s financial innovation process. The CBRC and any local government where a P2P platform is registered were supposed to supervise the activities and implement the rules. But they were seriously understaffed(註2). It was also impossible for the local governments to effectively oversee the platforms that operated across different jurisdictions throughout the country.

Most importantly, the localities formed symbiotic relationships with P2P platforms for rent-seeking and corruption purposes, incentivising the authorities to turn a blind eye to financial irregularities and even Ponzi games. This explains why the regulators have failed to ensure P2P lending platforms stick to their role as “information intermediaries” but not financial intermediaries.

What this means is that unlike a bank, which pools depositors’ short-term funds and lends them out in long maturities and has an obligation to pay back depositors even if the loans go bad, true online P2P lending simply uses a platform to match borrowers and lenders over the internet. True P2P lending also means that lenders are only paid when the borrowers repay their loans, and the lender cannot ask the platform for any form of guarantee and reimbursement if the borrower defaults. These are the critical attributes in distinguishing a P2P platform from a bank.

But in China, all these lines are blurred. Many P2P platforms are either Ponzi games from the start(註3)or operate as illegal underground banks. They pool funds together via the internet for lending, issue wealth management products that have maturity mismatches and even provide repayment guarantees. Since there is no due diligence process, investors/lenders have no idea what risks they are facing until suddenly the platform goes belly up. The CBRC did issue rules in August 2016 that outlawed these practices, but the eruption of the crisis in June 2018 clearly shows that there had been no compliance.

How worrying is the P2P debacle?

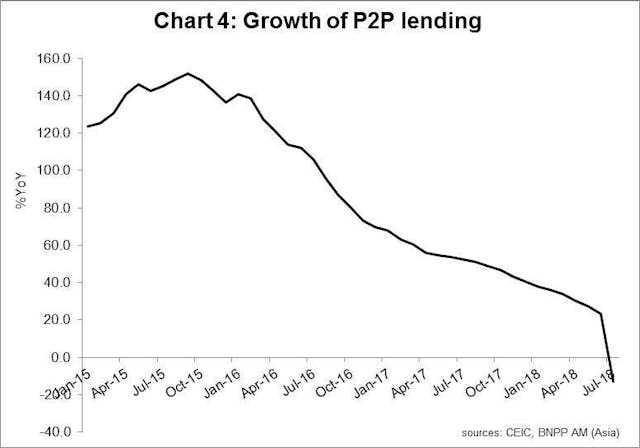

The P2P segment is small. As of July 2018, it only accounted for 0.7% of total bank loans and 0.5% of total bank assets. P2P loan growth has also been declining since its peak in 2015 (Chart 4). Only a tiny portion of the population, mainly the middle class in the big cities, has invested in P2P loans. So the crisis is unlikely to have any systemic impact on China’s financial system. Furthermore, new loans are increasingly hard to get due to both the government’s deleveraging policy and regulatory crackdown on the lending platforms. This means that bad borrowers cannot easily find another platform to lend them money to payback previous loans. So the P2P problem is unlikely to grow further.

However, the risk of social instability is still unclear at this point, as the losses from the crisis have become a socio-political issue that has added to President Xi Jinping’s policy headache on the back of slowing economic growth momentum, rising financial defaults and intensifying Sino-US trade tension.

Furthermore, the localities’ symbiotic relationship with the P2P platform has directed some of the P2P loans to government-linked projects. Failures of P2P lenders will cut off the flow of funds to these projects which banks would not fund. There is no data for tracking the share of P2P loans to government-linked projects, which is a very recent phenomenon. But we can use the share of the “others” category in the total source of fund for fixed-asset investment as a proxy. As of July 2018, this only accounted for 17%. This portion certainly also includes other shadow bank activities but not just P2P loans.

In a nutshell, the P2P crisis is a structural problem that Beijing has to resolve along with its financial modernisation programme, but it is not likely to become a systemic problem that could wreak havoc on China’s asset market. As of July 2018, there are still more than 1650 P2P lenders in China and further consolidation is inevitable. Obviously, investors should be careful with investing in listed P2P players, some of which are listed on overseas exchanges.

註1:“Xi’s Grip Loosens Amid Trade War Policy Paralysis”, by Willy Lam, The Jamestown Foundation, China Brief Volume 18, Issue 14, August 10, 2018.

註2:The CBRC admitted in private conversation in 2015 that they had only two to three full-time staff working on supervising, regulating and drafting rules for thousands of complex P2P platforms.

註3:The most famous case is the Ponzi scheme Ezubao, involving USD7.6 billion and over 900000 investors. See http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-02/01/c_135065022.htm