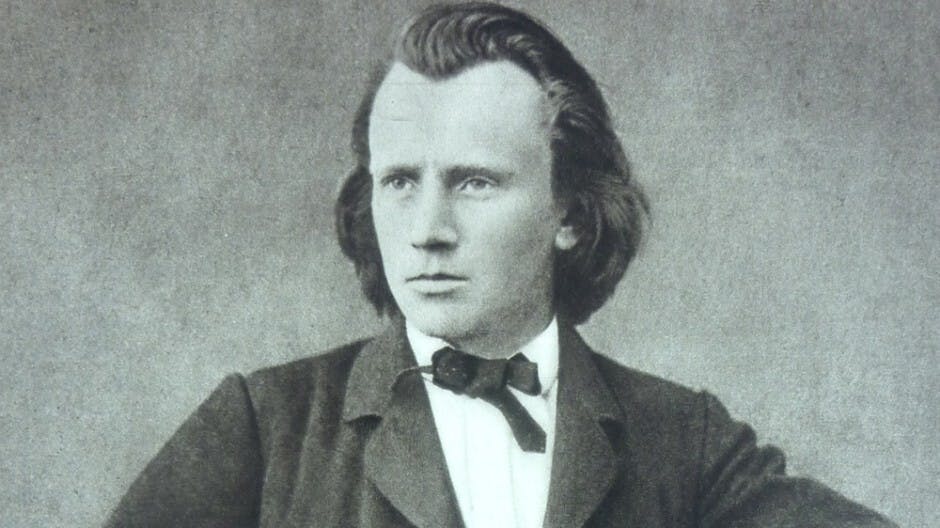

編按:本文出自作者12月4日「布拉姆斯音樂中的浪漫主義——畢永琴獨唱會」的宣傳單張。文章有中、英文版本,介紹布拉姆斯音樂、尤其是其歌曲(Lieder)中浪漫情懷。

Singing of Brahms’ (1833–1897) Lieder has always given me a very different feeling from that of Schubert’s (1797–1828). Both are important song writers of the Romantic period.

In my recent book on romanticism in Schubert’s Lieder (published in Chinese only), I attributed the root of romanticism to Kant’s (1724–1804) idea of “feeling of the sublime” when one finds himself before something which he cannot place under human reason in whatsoever way. This feeling of the sublime is not because there is a lack of reason or frame of reference under which one can talk about or think in terms of for the object, but the object, in front of him, simply cannot be reasoned because it is formless. Examples of formless “objects” are wonders of nature, catastrophes, depth of night, death, demons, etc. Kant called the feeling of the sublime an “intellectual feeling”. Man has it because he, by nature, is rational, i.e. relates to the world around him only under reasons. Here, for the rational being, he feels amazed, fearful, unsettled and speechless. It is not the fact that the object cannot be comprehended, but the object’s incomprehensibility that has alarmed him.

The feeling of the sublime was first captured in the western culture in works of art: the romantic paintings at the end of the 18th to first half of the 19th century. Then when this situation of a very strong feeling of something which one cannot comprehend got into the hands of the imaginative literates, romanticism took on a new footing: the bitter and forbidden love. The love is forbidden because reason does not allow it so. It is bitter because it is one’s own reason that has stopped him from loving.

The German poet and philosopher Schiller (1759–1805), in his book On Grace and Dignity (1793), suggested that there can indeed be peace in suffering (pathos): even when one suffers, his can feel graceful and dignified. And it is much more romantic if one loves sincerely but shyly, passionately but in secret, bitterly but in silence, in acceptance of failure yet forever hopeful. Here, shy, secret or silence only means there is no intention in the person, no matter how desperate he feels, to change the situation. It is not hope that has kept the person composed, but that his suffering is so great and yet he has succeeded to sublimate it to feel graceful and dignified, the most romantic feeling of all: peace in suffering.

If the youth in Schubert’s love songs loves shyly and in naivety, the protagonist in Brahms’ loves passionately but in secret. But one can only understand the meaning of this secrecy in the context of Brahms’ personality.

Brahms called himself “free but alone” (a motto that he borrowed from his life-long friend Joseph Joachim). He was known to be extremely reticent. He was reluctant to talk about himself and to reveal his feelings. He wrote better than he talked. However, people do get to know his inner world from his large amount of personal letters, diaries and memoirs. He was said to be a sociable person, but only among friends that fit his own passion. He loved his family and friends and yet was insensitive to the worries and pains of others. He himself has admitted to Clara Schumann that “towards friends I am aware of only one failing: awkwardness in relating.”

Brahms was attracted to sensitive and intelligent women, but he loved freedom too much to have wanted to commit to any relationship. The price he had to pay was his solitude. His Lieder Kein Haus, keine Heimat (No Hause, no Homeland) (Op.94/5), text by Friedrich Halm, perhaps, best describes his mentality in this. “No house and no homeland, No wife and no child, I whirl like a straw in the wind and the wild! Wave rising, wave falling, Now here and now there, If you care not for me, world, Why, then, should I care?”

Brahms’ music is known for its exceptional intensity and depth of feeling. His Lieder tells better his inner world if this cannot be expressed by him in speech. He resolved his solitude via the passionate words in his songs. The singing of Brahms songs requires a warm voice. As a song writer, he is a melody writer. Singing his songs gives one great musical and emotional satisfaction.

演繹舒伯特(1797–1828)及布拉姆斯(1833–1897)的歌曲一向都給我很不同的感覺。兩者都是浪漫時期重要的藝術歌曲作家。

在《舒伯特歌曲中的浪漫主義——純真情懷》一書中,我把浪漫主義的根源歸因至康德(1724–1804)的「昇華之感」,一種當人對着眼前物,用任何理也不能明解它時心中的感覺。此昇華感覺不是因為人看不明物,而是因為物本身根本就不能被明解。不是人找不到適合解釋此物的理,而是就算找來世上所有的理,也無法令人對該物有任何的一個說法,因為它根本就是無形、無邊界的。康德稱此「昇華之感」為一種人理智給予他的感覺(intellectual feeling),因為理性是人的天性:他必定是在理之下去明瞭身外世界。物在、理雖在但形不在,面對此情景,人會覺得既驚訝又不安,欲言但又無語。什麼物可以被稱得上是無形之物?大自然奇觀、天災、死亡、深夜、妖魔等都是。

浪漫之最 痛苦之情

以康德「昇華之感」為主題的文藝作品,最早出現在18世紀末至19上半世紀的浪漫派畫作中。但「理在但形不在」此情景落在文人手上,發揮空間就變得很大,不過,在文學作品中,無形之物的「物」指的多是人那大得不能被量化的情感,無論怎樣去形容它也只是在打個比喻。舒曼寫給太太結婚情歌 Widmung 歌詞的首句,「妳是我的靈魂、妳是我的心肝」便是這樣的一個愛的比喻。不過,浪漫之最並不是這種浪漫溫馨之情,而是浪漫痛苦之情;容不下情的不是認知事物之理,而是道德之理。浪漫是因為我情之大,痛苦是因為捆綁自己的理正是自己選擇要守的理。

當人在自己理性的枷鎖下、在情理之間掙扎、心靈痛苦時,德國文學、哲學家席勒(1759–1805)及時指出人其實是可以把其浪漫痛苦之情昇華至純真之情、熱情、苦情等。與其反抗掙扎,不如心靈平靜,人亦會因此表現得高貴,生活得有尊嚴。對想要但選擇不去爭取之情,存單純之心,雖仍敢於表達,但不打算改變事情。令人心境平靜的不是因為對事情仍存希望,而是人已無視那捆綁自己的理。

如果舒伯特曲中的少年愛得單純,布拉姆斯曲中的主角便是愛得熱情如火。但愛雖是真,卻志不在擁有。布氏經常借用其好友 Joseph Joachim 的座佑銘 “free but alone” 來形容自己。他寡言少語,不願表達自己,更不願向別人訴說感受。不過,後人不難從他大量的私人信件、日誌、回憶錄中得知其內心世界。他熱愛家人、朋友,和他喜歡的朋友交往,談笑風生,但對不喜歡的人和事,態度會變得毫不客氣。他亦直認與人相處不是他的強項。

布氏一生數墜愛河,亦直言不諱喜歡舒曼太太 Clara,但他更愛自由。多次有機會娶妻成家,最後都打退堂鼓。自由的代價是孤獨,布氏終身不娶。「我無家無鄉、無妻無兒,像一根稻草在野地裏一隨風旋轉!潮起潮落,時此時那,世界於我不過不問,我又何須理會世界中任何事物!」是布氏94號作品中第5首的歌曲,這可能是他內心世界一個很好的描述。

布氏雖然寡言少語、與人難於相處、最後孤獨終身,但他的音樂卻是感情豐富,他的歌曲旋律性很重,藉音樂、詩詞道出他情感的內心世界。演唱布氏的藝術歌曲聲音要較圓、音色要令人覺得舒服,唱者靠的不是一把甜美、輕巧的聲音。這一切若是出自內心的,演唱布氏歌曲會是在音樂上、情感表達方面一大享受。